At a Glance

- From late spring into summer, flash flooding is most frequent in the U.S.

- This is due to a combination of factors, including a slower jet stream and more humid air.

- Tropical cyclones can also play a major influence.

- Flash flooding is one of the biggest weather-related killers each year.

The frequency of flash flooding in the United States peaks from late spring through summer due to a number of weather factors.

The atmosphere is warmer and more humid this time of year in areas east of the Rockies, and hurricane season and the Southwest U.S. monsoon also play a role.

In the graph below, the thin bars illustrate the number of daily flood reports from 2007 through 2017, according to NOAA's Weather Prediction Center (WPC).

While flash flooding can happen any time of year, reports rose rapidly starting in late April, reaching a summer peak before tailing off into the fall.

WPC warning coordination meteorologist Alex Lamers noted about 75 percent of all flash flood reports in the U.S. occurred from late April through mid-September.

To be clear, by flash flooding, we mean only those short-fuse events triggered by heavy rain over a relatively small area, rather than longer-lived river flooding events taking place over days or weeks.

Flooding should be taken seriously because it's one of the deadliest types of weather phenomena.

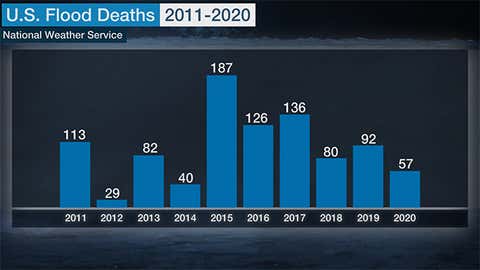

Over the past 10 years ending in 2020, an average of 94 people were killed by flooding in the U.S. That makes flooding, on average, more deadly than hurricanes and lightning.

Here's a closer look at what makes this time of year so prone to flash flooding.

Flash Flood Factors

Warm, Humid Air Is More Widespread

With the sun's more direct rays shining on the Northern Hemisphere, warmer air returns to an increasingly larger fraction of the country as spring progresses.

More water vapor can exist in warmer air and that increases the rainfall potential for both individual thunderstorms and larger-scale weather systems.

Jet Stream Slows, Moves North

The atmosphere's steering wheel for large-scale weather systems, the jet stream, both weakens and migrates into the northern U.S. and southern Canada by summer as the north-to-south temperature contrast weakens.

With generally lighter steering winds aloft by summer, especially in the central and southern U.S., thunderstorms and clusters of storms move more slowly. The slower the movement, the greater the rainfall potential.

Another result of this jet stream migration and weakening by summer is the absence of cold fronts sweeping the warm and humid air away from the southern U.S.

Thunderstorm Clusters

Despite the weakened jet stream, often times in late spring and summer, individual thunderstorms will congeal into a large mass of thunderstorms known to meteorologists as a mesoscale convective system (MCS).

While some MCSs can move rapidly, producing widespread damaging winds, others can move slowly if winds aloft are weak, triggering major flash flooding, particularly in the overnight and morning hours in the nation's midsection.

(MORE: Why These Thunderstorm Clusters Are Both Important and Dangerous)

The Southwest Monsoon

By summer, high pressure in the upper levels of the atmosphere usually sets up in the Plains, opening the door for increased moisture from the eastern Pacific Ocean and Gulf of Mexico to stream into the Desert Southwest.

Coupled with intense heating of the mountainous terrain, slow-moving thunderstorms can flare up over the high country of the Southwest and Rockies, then spread over lower elevations.

If the atmospheric moisture is deep enough, the slow movement of these thunderstorms could dump torrential rain, flooding normally dry washes and arroyos and triggering flash flooding in urban areas like Phoenix and Las Vegas.

Flash flooding can occur where it's not raining as water filling washes and arroyos moves away from where the thunderstorm struck.

(MORE: 5 Things To Look For During the Southwest Summer Monsoon)

Tropical Cyclones

You don't need an intense landfalling hurricane, such as Category 4 Hurricane Harvey in August 2017, to produce flooding rainfall.

You just need a slow-moving tropical cyclone, whether a depression, storm, hurricane or remnant.

It was Harvey's loafing near the Texas Gulf Coast for four to five days after its landfall that led to the rainfall flood disaster in Houston, Port Arthur and other locations.

A much weaker tropical cyclone, Allison in June 2001, wasn't technically still a tropical cyclone when it unleashed rain that pushed flooding in Houston to a $5 billion disaster.

Incidentally, this isn't just a concern along the Gulf Coast and East Coast. Remnant eastern Pacific tropical cyclones have triggered some of the more severe flash flood events in the Desert Southwest over the years.

In July 2015, torrential rain seeded from what had been Hurricane Dolores triggered flooding in the deserts of Southern California, washing out a section of Interstate 10 east of Palm Springs.

Take all flash flood warnings from the National Weather Service seriously. Never drive on a flooded road and avoid walking through flood water that could be contaminated. Know how to get to higher ground quickly if you live in a flood prone area.

The Weather Company’s primary journalistic mission is to report on breaking weather news, the environment and the importance of science to our lives. This story does not necessarily represent the position of our parent company, IBM.